Onlangs was het eerste deel van de ‘Unpublished Bill Clifton interviews’ te lezen. Ik heb tot dusverre niet kunnen achterhalen waarom we niet verder zijn gegaan met het project waar we destijds mee gestart zijn. Achteraf redenerend denk ik dat het de Bear Family CD-box en het daarbij verschenen boek (waar Rienk Janssen veel aan meegewerkt heeft) een factor geweest is, maar dat is slechts een gok. Ik moet bekennen dat ik me nu pas – jaren nadat de interviews gemaakt zijn – echt in de tekst ben gaan verdiepen. Ben het dan ook helemaal eens met de reactie van Bert Nobbe bij het eerste deeltje van deze nieuwe serie (de vorige post). Die ging post hoofdzakelijk over de dingen die Bill Clifton had gedaan in de periode tussen de Carter Family Conference in Londen en het moment dat we aan deze interviews begonnen. Het zou inderdaad jammer zijn dat al dit materiaal nog jaren verder in de lade van mijn bureau ligt te verstoffen. Vandaag dus deel twee…

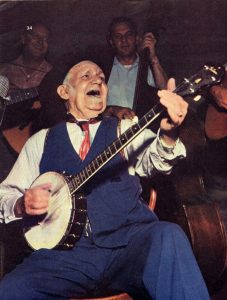

Bill Clifton and Uncle Dave Macon

Transcriptie:

What does gospel music mean to you? When I listen to that record, ‘River of Memories’, and I listened to all your other records, which I like very much, but I think when I listen to ‘River of Memories’, I think you put a lot of soul into it. It’s the one that means the most to me of any of the recordings I’ve done. And what does it mean to me? Yes, spiritually it means something to me, but it also carries a lot of memories of people, places, and times that I shared the music, some of those songs, with people in the Church of God. I used to go to the Church of God when I was a teenager. They had wonderful music; they always allowed me to play. I was ‘Brother Bill’ and they’d bring me up to…. ‘Bring his guitar up and get Brother Bill up here and he’s gonna sing us a song and we’re gonna join in’. And there would be a fiddle player and a banjo player and maybe a mandolin player, another guitar player perhaps. All acoustic music.

They didn’t play bluegrass music without knowing it? Well, they didn’t play bluegrass. They played more old-timey style. There was no bluegrass music in those days. I’m talking about the forties. Yes, Bill Monroe was around, and nobody had a term for it yet. The term didn’t arise until the early fifties. In fact, it might have even been the middle fifties when I first heard it. I don’t remember exactly but it was after Elvis Presley. I know that. So, it could have been somewhere in ’53, ’54, or ’55, somewhere in there, that the term ‘bluegrass’ came about. And the only way that any of us can figure out why it came about was because of Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys. Who were the only people on the Grand Ole Opry, at that time, when Elvis Presley was so strong, when he first came out; Monroe was the only person on the Opry playing that kind of music. So, when people didn’t know what kind of music, they liked it was kind of … ‘Well, that sort of bluegrass band thing’ that they heard on the Opry which was different than any of the other things on the Opry at the time. So, my feeling is that that’s when the term arose and who coined the term, I have no idea. It just came about, and it was used, and it was understood. And people could accept: ‘Well, yeah it means Monroe or that kind of music, you know’.

It’s recognizable as well, isn’t it? And that’s part of its success? Oh yeah, it’s very recognizable. Although Bill, if you ever asked Bill about bluegrass music, I mean Bill was always very adamant about it. He would say: ‘bluegrass music hasn’t got anything to do with the banjo. It’s the fiddle. It’s the fiddle that makes bluegrass, you know’. Well, of course people who listened to Bill Monroe when he had an accordion player (when Sally Forrester was playing the accordion), and Stringbean was playing old-time banjo and… His first record, ‘Kentucky Waltz’ was without, yeah Stringbean played a little banjo but not much, you know. I mean it was just a tinkling of the banjo in the background somewhere. It was mainly fiddle and accordion and then Earl Scruggs came along and really changed it. Changed Bill’s sound.

Might I say that the mandolin breaks were different as well? Oh yeah. Well, the mandolin breaks were always important. I mean, Bill’s mandolin [playing] of course is based a lot on his uncle Pen’s fiddle playing and he got a lot of his ideas about tunes and things from James Pendleton Vandiver (Uncle Pen). But his approach to the music really had nothing to do with the banjo. But when Scruggs came along and knocked out the Grand Ole Opry audience completely, where they had standing ovations one after the other, of course that’s when that great story about Uncle Dave Macon came along. Which I don’t know if you want me to digress in that. Do you know that story about Uncle Dave?

No, I don’t… Well, Uncle Dave Macon was the banjo player on the Grand Ole Opry, and he was also the funny man. He always told the jokes, and he was the one that got the laughs. And he was the singer. For a long time, until Roy Acuff came. And then Roy Acuff sort of became the singer. But Uncle Dave was still the funny man, and he was still the banjo player. Well, when Earl Scruggs went to work for Bill Monroe… Earl of course is one of these poker-faced people, he never smiles or anything, you know. He’d just come off the stage and it would be hot, and he would sort of wipe his brow. And there would be a standing ovation out there, in the audience. Earl wouldn’t pay any attention, you know. He’d just sort of wipe his face. Well, one day he was coming back off the stage and Uncle Dave never bothered to learn his name. He always called him Ernest, instead of Earl. He was having a standing ovation out there and he came backstage and, as he walked off, Uncle Dave said to him: ‘Well Ernest, you played some good banjo out there but you wasn’t a damn bit funny!’ So, Uncle Dave was still the funny man, he wasn’t the banjo player anymore, you know, and he wasn’t the singer. I always liked that story.

Man, o man wat waren en binnen wie goud! Gain aine was een betere interviewer as wie dreien. Harry ik geniet!!

Ik vind dit ‘Bill Clifton project’ ook eens van de leukste dingen van de laatste tijd! Ik heb destijds nooit zo goed naar de CD’s geluisterd (dat zou ik nog een keertje doen – kwam het nooit van). Ik geniet enorm van Bill’s verhalen over ‘vroeger’ en vind dat dit materiaal het delen ook meer dan waard is!

Deel 3 is ondertussen ook te lezen…