We artists are very lucky people you know, we get something that a lot of people in this world never get. We get microphones! – John McCutcheon

Is there a difference between festivals over here in Europe and the festivals in the United States? It depends on what kind of festival you go to. A festival like this one here in Diever is focused on a particular kind of music. I was also at a festival in Italy, near Milano. It was a festival that the people behind the magazine ‘Hi Folks’ had put on and that festival over there, as well as this one here, was focused primarily on an American type of music. Most of the festivals I go to outside of the United States tend to be festivals where there’s lots of different people from all over the world who’re just doing their particular kind of traditional music. I for myself just happen to be a representative of an American musical form of some sort. Whatever it is that I do, I’m not exactly sure how to classify it. Because the music that I play is not pure bluegrass, and it’s not strictly old-time either although a lot of the stylizing that I do – you know – my banjo- and fiddle-styles are old-time. Whit a festival like this, one thing I can do is, because I learned my music directly from a lot of people you all listen to on records, I don’t know how you call it in Dutch, by I mean that I can ‘flesh it out’. This is making the music come alive to an audience and putting it in its original context. When I went to someone’s house I learned a lot more than just his music. I learned what part of someone’s community and what part of someone’s life the music took up. Every someone lives in a culture and in the United States the music culture is predominated by rock and roll and country and western music and these musical forms are constantly being modernized and all those things. I don’t know what it is that makes someone play this kind of music that a ‘normal’ American would think is very old-fashioned. And it’s really intriguing to find out that the people who have kept doing this this throughout the years see a real important role for themselves in telling young people about their own history. We don’t know very much about our own history in the States. That’s why a lot of the records that I do, the most recent one [‘Gonna rise again’], the reoccurring theme in almost every song is that we learn from our past. You know, I listen to the radio these days a lot and I listen do contemporary music. When I do a program I want to make it relevant for everybody who is sitting out there, not for someone longing for the good old days. I’m not a nostalgia show! The music that I learned, I didn’t learn it from records or out of books, but I learned it from real human beings! Whenever I play ‘Sally Ann’ on the fiddle, Beechard Smith, the man who I learned it from; he’s very much alive for me. And he also was the person who was thoroughly modern. But his music fits into the structure that the old is not replaced by the new. It just giving it a new perspective…

On the other hand, this present time will once – in the future – be history. So it’s not only looking back, but also looking around to see what’s happening at this time… And looking forward as well. There’s lots of different ways in which artists of all sorts, musicians and sculptors and poets can and must contribute to their society. There are many parts in the United States for instance where this music is just as foreign as it is to the average person here in The Netherlands. You can go to New York City, and I’ll be playing in a nightclub there. And I’ll start talking about a coal camp somewhere, or someone who works in a cotton mill, and all of these people who have paid twenty dollars to com in and sit down and listen to me doing a show. It’s just as far away from their reality as it would be to the people here in Diever…

So ‘your’ reality is really kept in the mountains where there was or is not the amount of contact with other people and where there’s probably not that much influence from the outside (world) to wipe it away. They stay there… Of course there’s things that are very contemporary happening in the mountains today. Like what’s happening at Jeanette Carter’s Family Fold. There you have a watermark of what’s happening culturally in her county nowadays. She’s not trying to keep the old days alive. It’s just what she likes and what her neighbors like. And at the same time her son can sit down and play her grandfather’s guitar and play ‘Are you tired of me my darling’ or any old Carter Family song. But then the following night, he’ll pull out his electric guitar in a bar, and play with a country band and it all somehow makes sense. You know that the line between the old and the new is not as clear there and that’s one thing I like about it. It’s just the young and the old living side by side. As they must… As they should…

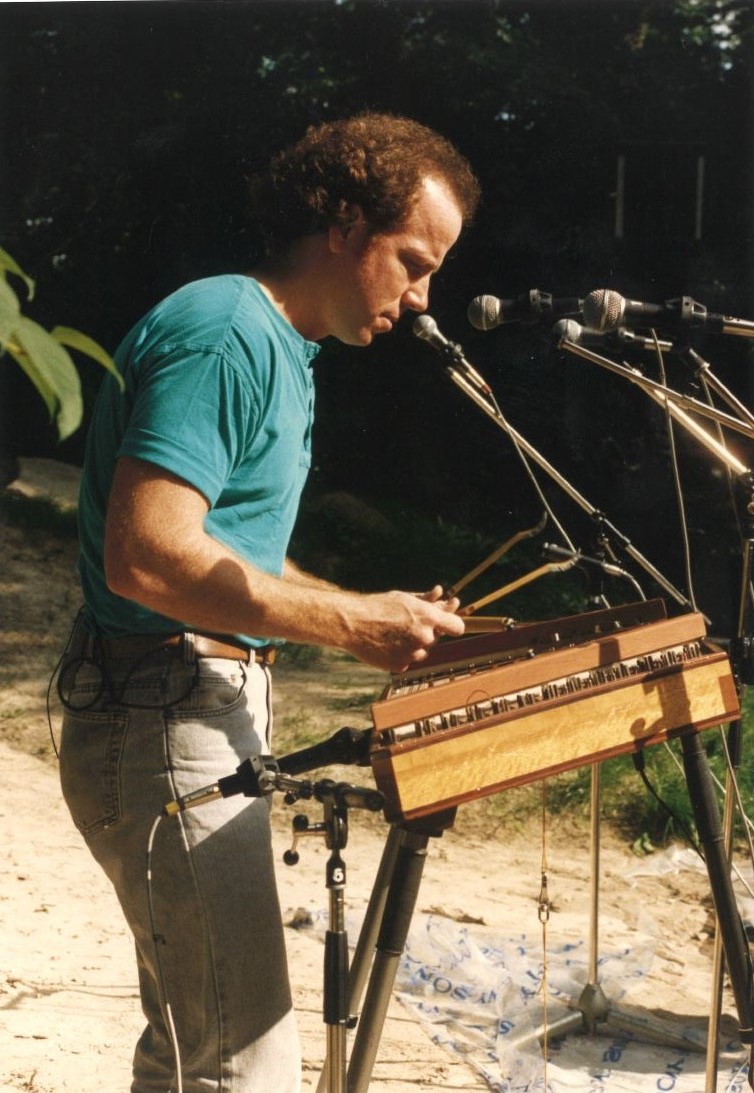

But isn’t it true that you are one of the few with this attitude today, with this feeling towards the more… Let’s say the history and the way of life that you’d like to preserve. There are people like Si Kahn of course. He also has a very sincere message for all of us I think. But his message is more a social one, one of a combat against all the rules and laws and things that oppress people… Well, I think that one of the things that… Well, Si and I are similar in many ways in that regard. Because there’s the whole attempt to harmonize American culture. And not only in America, but all over the world. It is this attempt to make everybody the same that I react against. I come from a country where our strength has always been in our differences. We’ve got people from many different cultures and many different parts of the world… And there has been a tremendous effort, specially in the last seven or eight years to get everybody to forget their own languages; to forget their own cultures; to just be Americans. And I’m maintaining that we’ve always been a country of immigrants and that we should be proud of our cultures and be proud of our differences. I’m not really trying to preserve anything, because it’s not my culture. I come from a working class family, my mother was raised in a working class family. I just believe that people ought to have an appreciation and a pride in their histories, because if we don’t know and preserve our past, we don’t know where we’re going. This is the reason why in my concerts I will have some songs that will tell talk about our history, but also some songs that will talk about the future. And I sing for the children and I sing for the very old people. And I like that. To some people in the United States I’m just a hammered dulcimer player, to some people in Scott County I’m a fiddle player, to some people I’m a political musician, to some people I’m a songwriter, to some people I’m a children’s musician, and it’s just all… And I like that…

And does all of that fit into your definition of being an artist? To me it does. You know that we all have created these boxes so that other people who market us can sell us. Because I don’t fit into just one box, it’s confusing for them, but for me it’s great because when I’m doing a concert in the States there’ll be little children and there’ll be very old people and there’ll be people who just come to listen to pretty sounds and there’ll be people who’ll come because I sing for their Union or whatever. There aren’t many things in my country where lots of different, very different people can get together – a sporting event maybe – and I really relish that!

That’s what makes the Carter Family Fold so unique, right? Yes.

Do you read music? I’m asking this because there’s so much traditional music, like fiddle tunes, that are never written down. Isn’t there a way that these tunes won’t get lost over a period of time? Well, I do read music, but there’s an old saying in the mountains that… Some college professor asked an old fiddle player from the mountains: ‘Can you read music?’, and the fiddle-player said: ‘Not enough to hurt my playing…’. I didn’t learn to read music as a child, but most of the music that I’ve learned, I’ve learned by ear. Because you are not able to catch all the nuances on paper, I’ve always looked upon written music as a road-map, or a script. Two people can read the scripts and have totally different results and feelings about it. And I treat written music – I don’t use it very much – well on this record here [‘Winter Solstice’] I did some stuff from Händel’s Messiah and I used sheet music for that. But by and large I’ve learned my music by ear.

About your instruments John, you play a lot of different instruments. Did you learn your songs on all of the instruments you play? Or do you play them on the same instruments as the people you’ve met? Oh no, that was quite accidental. I started off by playing the guitar, and then a number of years later I started playing the banjo. Once I played the banjo, I’d spend a lot of time with fiddle players and eventually I got to playing the fiddle because I was around fiddle players so much. In the early days of my performing I used to rely a lot on the fact that I could play a lot of different instruments, that was sort of my act… and I would spend a lot of time going from instrument to instrument. But now that doesn’t impress me as much anymore and when I try to think of what songs I want to sing for an audience, I’ll sometimes go through a whole evening of playing and I won’t play the fiddle or I won’t pick up the autoharp, or the banjo for that matter… It just depends on the fact that I look upon them as tools and it’s like with someone who speaks several languages, once you’ve learned German for instance, Dutch might be easier to learn for you. Once I learned to play the guitar, the banjo was a lot easier because I already had the coordination. Once you get around to them, it’s not unusual to see someone who can play the mandolin and the fiddle because the fingerings are the same, or someone who can play guitar and also mandolin because they’re good with the flat-pick.

Do you also do workshops at the festivals or gatherings you perform at, or sometimes like these week-during kind of camps where they’ll teach you different styles of playing and different instruments? Well, I used to do that a lot more than I do it nowadays. But I do a lot of workshops at festivals because I enjoy talking about how I think about music and how I play and how and where I learned to play. A lot of people aren’t very good at that and that’s another thing that I’m lucky enough to be good at. I was a schoolteacher for some time. And I think that there are a lot of things that I do when I’m on the stage that someone else also does when they’re on stage. You say, you know, gosh, how does het do that, or he’s singing that song… What is it about? You raise a lot of questions in a listeners mind when you’re performing. I’m always interested in… That people understand what I’m singing about and what I’m doing. So that they get the full meaning of what I’m saying and singing, and also that they can maybe can get some of the enjoyment that I get out of it. And also the workshops that happen at festivals are – I think – very valuable. I’m sure that at this festival, if we had said okay, we’ll have an hour where everybody can come and sit around and ask John about the hammered dulcimer that we’d have a lot of people sitting here…

Well, that was going to be my next question. Do you think that there is a difference in the audiences here and in the United States? Because we’ve been trying to get the workshops goings for several years, but it hasn’t worked out yet. It would turn out to be a mini-session, a mini concert for the musician involved in giving the workshop. He would be hardly asked any question. I think that a lot of it depends on how the workshop is run by the artist. Like I said, a lot of people are used to just getting up on a stage and performing and so when they get in a small group and have to talk about what they’re doing, they don’t know what to do, especially the performer who is part of a group. I talked to a friend of mine, and he said: ‘I’m the banjo-player. In the group I never have to talk when I’m on the stage, and all of a sudden they put me in a workshop where I’m supposed to talk…’. And it was very difficult for him. But I’m a solo-artist, I talk all the time when I’m on stage because it’s very informal what I do, so I think that a lot of it is – like I said – in how the workshop is run and how interesting the subject is… If we had something where you’d say to the audience: ‘Come over to the parking-lot in this corner and for the next hour John will be there, answering your questions about the hammered dulcimer’. I’m sure that there’d be lots of people with lots of questions. Even people who had seen the hammered dulcimer before. I mean, I play very, very different from anybody else in the States that you might know. In the States I get questions like: ‘What’s that pedal you’re stepping on?’ and: ‘Why are you beating on the wood?’ and: ‘Where do you come up with these crazy ideas for the things that you try?’ And I enjoy meeting people like that, and a lot of the stories that I tell, a lot of the songs that I write and a lot of the inspiration for why I do what I do comes from the people that I meet. I’m very glad I’m not really famous, because then I would have to be separated from the audiences. And that would be really difficult for me.

But do you think, because over here we’ve just been playing our records for such a long time… Because there were no concerts to go to and there were no performers to see over here, that it has to do with his upbringing of ours that the workshops over here in Europe don’t work as good as they do in the States? Well, I think it’s probably the same way in the States too. When the people started coming up to me, sometimes it would be with a question and sometimes it would be just to say: ‘You know, I have all of your records and I really like your music…’. And so I’d be embarrassed, because it is really embarrassing to have someone come up to you and praise you. As much as you like it, you don’t know what to say when it happens. I’d say: ‘Well, eh… thanks a lot’. Without really realizing how much courage it must have taken these people to come up to the performer that they’ve just listened to. I keep thinking back to the people who I thought were really famous and how I went up them and how tongue-tied I’d be. I’d feel stupid for I knew I had said all the wrong things. It’s hard for any person. That’s why in most of my records I write inside of the sleeves, I have little stories on the songs, and more recently I started putting all of the chords in there with the songs, so that the people can learn the songs themselves if they want to. I just try to make it accessible to them, because I think it’s important that people feel as though they aren’t any different from other people either. I think that we’re important in our community, just like the plumbers, the farmers, and the teachers too. In the United States, and probably in The Netherlands too, the artists are considered to be either the lite or they are the insignificant, and there doesn’t seem to be a way for any artist to just be normal like any other person. It’s hard to combat against that, but I feel that it’s important to do just that. It’s the only way that’ll keep you from feeling like a star and that lets you be just a regular worker like everybody else. Because I think that musicians have to be workers too.

When did you start your career in music? Was it by accident, or did you plan your career this way? Sort of, because back in the sixties when folk music was very popular in the States…You know, people like Bob Dylan; Pete Seeger; Peter, Paul & Mary (‘Puff, the magic dragon’) and everybody else. Lots of us young kids started to play the guitar in those days and that’s the time when I started playing one too. And then gradually I learned from there, and because I loved it, I learned very quickly and I was hungry for new things all the time. I just kept hearing new sounds and discovering new music in those days. And then when I started visiting the people in their homes, then all of my doubts were over. Because then I knew that this was really what I wanted to do. And this was so very different from learning from records, and from the learning from books. Here there were real people who were… You know when I sang… All of a sudden when I heard Roscomb Holcombe singing ‘Little birdie’, I realized that it wasn’t this voice on a records, but is was some person I knew very well and whom I had helped build his bathroom. We’d go on these trips together and we’d have supper together. We were friends. I learned where he learned that song and all of those things that really meant something to him. This whole process started to make the song mean a lot more to me than it would have done otherwise. And going through that process makes music come alive for you.

Dan Crary once told me in an interview that in order to be an artist the music’s got to be in your head. It doesn’t matter which instrument you play, if the music’s in your head, you can play any instrument. Because the music has got to come out of your head one way or the other. It’s got to be in your heart too.

But then I told him that I have tried to play the guitar for many years, but it seemed that I have no talent for it. He told me that if I kept on trying it’d work out sometime… I don’t agree with him, I think it’s something that you’ve got, or that you haven’t got at all. I think that there is a lot of difference between having the music inside of yourself and going through all of the athletics of putting your fingers at the right place at the right time. Because there also are those people who really love music, who talk about it and help to form people’s opinions about it through the magazines and those people sometimes don’t play an instrument or someone who sings a song. I learn as much about music from my audiences as I do from other musicians. You know, if I have written a song, I might think it’s a real… I might think it’s an okay song, but then someone from the audience will come up to me and say: ‘You know, that song… that song really, really meant a lot to me’. And you didn’t know that. Another musician can come and say: ‘Oh, that song… that has a beautiful melody, or I like the chord changes’. But when someone who hears it says: ‘You just sang my life there on that stage… You know, that makes up my mind about that song’. Then it works. And then it doesn’t matter anymore whether the melody is good or that the chord changes are good or that the rhymes are perfect. I know that people want to be moved more then they want to be impressed. And so being able to play the most notes in a minute isn’t as important as being able to play the right notes at the right time. It’s like, well, did you know Beechard Smith, or did you ever meet him?

Well, I saw him on the Appalshop film and I remember the first time that I was at her festival, that Jeanette Carter said to me: ‘It’s a pity, but Beechard Smith just died a short time ago’. He had died a couple of months before that festival. Well, he was a fiddle-player who wasn’t real smooth but he was of scratchy, but he was so soulful…

I watched his face on the film, his expression as he played… And just the way he played, he moved more people than most of the fiddle-players I’ve ever heard and he wasn’t the prettiest fiddle-player at all. He didn’t play fast, but he played with such passion that the people just were… I don’t know what that guy did, but he really did it…

I have the same feelings with Peter Rowan, he has such a strong personality and he really touches you with the music he makes…

I heard you talking about workers just a minute ago; while listening at your albums through the last couple of years I noticed that the workers of the world are getting more and more of your attention. I was just wondering where all of this compassion with the workers comes from? What made you make this decision? I think it was very natural because of the people with whom I was going to study my music with, they were just working people and we would only study after they’d been working all day in a mill, or on their farm, or in a coal-mine or something. When they came home then we’d play music. And after that we would talk about what they did in the course of that day. I felt that that was a much part of my musical education as how to play ‘Sally Goodin’ or something. Because here I was, someone who was privileged enough to make my living out of playing music. But these persons, these teachers, they were much better musicians and artists then I was, so much more so that I wanted to come and learn from them. They were making their living by mining coal. And their music reflected that kind of living. They weren’t playing their music to make money. They were playing music because they had to, for what it meant to them. And a lot of the stories that I heard from these people ended up formulating my opinions about what music I liked and what I wanted to do… Because we musicians are very lucky people you know, we get something that a lot of the people in the world never get, we get microphones… And we get an opportunity, like all artists get, to. As we get out upon that stage, to paint our picture of the world. The picture of the world as I se it is one where we have respect for our traditions and there’s respect for each other… It doesn’t come naturally, it takes a lot of hard work. There aren’t enough outlets for everyday people. That’s what folk-music has always been about. It’s not the music from a certain area of our country or from a certain class of people. It’s the people’s music. I just want to tell the whole story.

Is this also the reason for the fact that a lot of these songs where you pay attention to the workers are politically involved songs too? Well, my work has always been politically involved. I just didn’t know how to talk about it well enough on stage. I hear a lot of these people who get up on stage who are doing a ‘political act’. I always saw that as an attempt to impress the people with how ‘political’ they were. With me; I just want to get results! I’m not going up there wasting my time talking about something just because I want to say it. That doesn’t help us anything. I want to help the people to get a little understanding about some people that they maybe don’t know anything about and make these people more human to them, because that’s the only way (in my opinion) that the people are going to change. In the States for instance, I just put out a series of records with music that I’ve recorded in Nicaragua, because the people in the States, normal people, don’t know anything about that. All they ever hear is the government’s opinion and that’s very confusing to the people. One reason for people not getting along with each other is that they don’t know anything about each other. So, in recent years I just feel that I’ve learned to that much better than before. Not all of the songs that I’m writing are political. I don’t know… every song that you’ll write reflects something that’s political in some respect, I guess. Even if you write songs about your children being born. You know, I’ve just finished a new children’s record and on the next record I’m going to do… All the songs are going to be about the sea. They’re not going to be songs that endite the government’s policies, but they’re going to be just little slices of someone’s life. To me, that kind of activity, bringing people closer together to people that they don’t understand or didn’t know anything about, that’s political work too. Just telling the people about folks you hear about.

Can you see a political change in the United States over the last couple of years? You mean… Well, since Ronald Reagan is in power it’s been very difficult. A lot of things have regressed, a lot of things have gone backwards. But I think that there is a lot of feeling among a lot of people now, that we do have the power to influence some policies. For instance, there’s been… The reason that the United States aren’t more involved militarily in Nicaragua is because of the people that don’t allow it, and that’s been an important development in our country. And to get the people together just to help one another. You know, people are getting very concerned… Talking about American farming, for instance, may seem a million years away to people over here, but it really hits the people that make their living with farming very hard. Lots of people are talking about it in the United States because things are changing so fast and the people don’t like it and they can’t do anything about it. When I go around, I sing a lot of songs about workers – just as you were saying – and the people will come up to me. Every year, I go to a festival in Kansas. It’s a farming area there and I’ve been singing songs about farmers there for years. The people, farmers, will come up to me and say: ‘Here are some poems I’ve been writing. You seem to be interested is this sort of thing and I thought well… Maybe you can read them and tell me if they are any good’. Or someone will give me a cassette… A while back I heard a rather cynical joke from one of these farmers. He asked me wat the difference was between an farmer and a pigeon. The answer was that the pigeon could still make a small deposit on a tractor. I think that that kind of thing is happening more and more in the United States. I also think that that’s very powerful. The people fee like: ‘Well, okay, I’m not a professional, but I’m just going to write a little poem about this and how I’m feeling right now’. And even if it doesn’t do anything but it lets them feel that they’re not crazy anymore. I think it’s really important…

Lately I saw a program on television where a farmer killed himself so that his wife and children could benefit from the insurance policy. I think that you’ve got to come a long way to be able to do such a thing… Well, in fact on my latest record there’s a song about that very thing. This is a real thing about the American Dream, the same thing that everybody always talked about. Because they said that if I worked hard and I was a good person, and if I dis this and this and this to help our country, I’d make it… And I did this and this and everything else they told me to do, and I’m still not making it. And the president gets on TV and says that the economy is growing better and better, but it isn’t. all of my friends are out of work, and I’m losing my farm… And then the people start blaming themselves. So, when people are able to write their songs and their poetry and feel like they can talk about their own lives and the things that concern them, that helps them a lot. That’s what Folk music has always been about. I just mean that someone had to write ‘John Henry’, for the song didn’t just spring out of the ground. It was man against machine in those days, that’s been an age old thing. I think that that’s the reason why a song like ‘John Henry’ has been so popular. It has more than just a nice melody, it’s the story, I think… ‘A man ain’t nothing but a man’. Now, that’s a powerful line, that’s a very powerful line…

And you can make a living for yourself and your family by playing this music? Yeah, amazingly enough. Well, over the years I’ve played for lots of different kinds of audiences. So now I’ll do hammered dulcimer arrangements with a classical orchestra, then I’ll play for children, and then a concert in a theatre…

Okay, well acoustic music here in Holland has died about ten years ago. We’ll have a little festival here and there, but that’s it. It’s almost over… I’ll be honest with you. Not everybody is as lucky as I am. I’ve been very lucky. I’m a solo artist. My record company really pushes my records which really helps. And I’ve been lucky enough to learn a lot from people from whom I’ve learned. I’m very lucky, perhaps it’s a given talent, but there’s a lot of luck to it as well.

I think it’s the audience also. They want to hear your kind of music, and I think that over here in The Netherlands there’s not much of an audience for the things that you do. Of course, the music that I play is American music. If you’d take the average person here in The Netherlands: ‘why don’t you like American country music?’ Then they might very well say: ‘why should I like it?’

Yes, but I think that if you’d ask such a question, the people start to think of names like Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers and all the other ‘rhinestones’. There are festivals – in Germany for instance – where you’ll see pistols and all that macho exhibition of all sorts of different things and behavior. The people over here tend to associate that with country music also, but the result of all of this is that our music is getting a ‘bad’ name. it’s been associated with a very right-wing kind of thinking and attitude. You know, the funny thing is that we have the same differences between right- and left-wing thinking in different areas of the United States. I’ll go to a bluegrass festival and I’ll be hired because they like a solo-artist, someone who plays old-time music, someone who can relate to an audience. And after six hours of pum-pum, pum-pum, pum-pum, pum-pum-pum, the people are glad to have someone come up there on that stage and play the hammered dulcimer and do different songs for them. Also I find that I don’t change my program all that much, when I’m playing such a festival or when I’m playing for a folk-music audience. Because a folk-music audience is much more progressive compared to a bluegrass audience in the United States. And when you talk about the rights of farmers and the rights of workers and so on, that’s something that everybody can relate to in any part of the country, regardless of the political party they believe in. You mustn’t put it in a way like: ‘you should do this’, or ‘this is just fair, this is life’. I’ll say: ‘I’m not going to tell you what to do, but here’s a picture on the way someone works, this is a day in someone’s life. And I’m not going to tell you what to think about it, but here it is. I don’t have all the answers, I just happen to have the microphone!’

Yes, but you can warn the people what might become of the society, that’s also in the songs that you sing. Am I right? Yes. It’s like in the song ‘Christmas in the trenches’, the song I sang for you all last night. I’m not saying that you should think this about that song, but I’m just trying to take you inside that man’s head. You (the man in the song) just went through all this, how can you ever be the same again? That’s what life is about!

Just like in Hazel Dickens’ songs. Exactly. She doesn’t tell people what to do, she just says: ‘here’s somebody, this is a true story. And I’m not going to tell you what to think or what to do, but here it is’.

Do you know her? Yes. Hazel’s wonderful. She’s great!

Who are you musical heroes? Not only in folk music, but bluegrass as well… Gosh, there’s so many names of people that your readers would know of course. It’s impossible to like American traditional music and not pay a debt to Ralph and Carter Stanley and Bill Monroe. But I also like a lot of people in the old-time world. People like Tommy Jarrell, The Carter Family and Uncle Charlie Osborne. Also a lot of the people that I’ve met, people that don’t play on any stage, but people that just sang a song or said something or the wat they played a certain song. You know, music continuously changes my life. Yet, there are also people who aren’t musicians at all, who are musical heroes of mine. People that just helped me to figure out how to do the things the way I do them. They’ll come up to me and say: ‘John, those songs you’ve been writing today… I’m really proud of you…’. My mother also always said that. It helped to keep me going in the same track and it let me know that I was doing the right thing for me to do. In this line of work, especially if you are a solo artist, you don’t know. You make up how to do this as you go along, there’s no role models, there’s no schools that you can go to. There’s no apprenticeship…

I think that we over here owe quite a lot to Bill Clifton. He was one of the first ‘traditional artists’ who came to Europe and het let us know about bluegrass music. Of course, he came here with the Carter Family tradition that he loves so much. I think that Bill Clifton was very important for us here in Europe. He was that in the States too. But there are also many people who I came in contact with, who aren’t in folk- and bluegrass music at all. People like Pete Seeger. Everybody who plays acoustic music in the United States today has more or less been influenced by him. Because he kept going after he had been black-listed, even after he had been called a communist. They wouldn’t let him go on the radio, they would not let him go on television. But het still kept on playing. Het went out to the young people and my generation was raised on his music and his whole perception of: ‘here’s a traditional song, here’s a contemporary song, the belong together!’ That was a very, very important influence in the States and he’s been a big influence of mine and many other people. As well as someone like Bruce Springsteen now, who is singing songs that are folksongs in many respects. His album ‘Nebraska’, that could have been… Is Woody Guthrie was still alive, that would be the kind of album that Woody Guthrie would make these days…

Definitely. And he’s doing ‘This land is your land’ as an encore in his concerts with just… With no instruments at all and het gets the whole… He gets 60.000 people singing it and thinking of it in a different way. A lot of times when people come to my concerts they say: ‘O yeah, I heard Bruce Springsteen do that song. Maybe this music isn’t so weird after all…’. That’s an important contribution… John Cougar Mellencamp, let’s look at his latest records for instance. He has hammered dulcimers and accordions and acoustic guitars and Dobro’s on it. People like that are exposing a lot of people to American acoustic music in rock and roll…

I sometimes read in other interviews that people travel a long way to meet the older musicians, like Frank Cocheran or Tommy Jarrell. Did you do that also? You see, I lived right down there, so I was part of it… I could go there in the afternoon and be home at night too. It was like visiting your neighbor… And that’s a very important part of how you start thinking about music, because when you visit somebody in his home it’s not something that’s just up on the stage. You go visit somebody in their home and you’ll find that it’s part of their life, not just pretty sounds. There’s something about playing music together that’s very liberating. It’s like you’ve gotten a key that opens you up.

I think that we and our musicians are too shy, because everybody is looking up to the ‘American stars’. We’ve got good groups over here in Europe too. The fact is that non-American players aren’t just imitating the ‘American stars’, but those thoughts you just mentioned before become part of their way of feeling and thinking about making music. Well, I can see that there’s still a barrier, there’s still something like: ‘they’re from the States where the real artists come from’. The group that Theo played in, ‘Jerrycan’, had am album that was a highlight album in the Bluegrass Unlimited. So I think that was a good album. But still, when Jerrycan performs somewhere, the people say: ‘oh, it’s Jerrycan. It’s all right, but so…’. Oh yes, that sort of thing happens a lot in the United States. When I play at Janette Carter’s Family Fold for instance… Now… Now that I don’t live there anymore, it’s become a very big deal and the pace is overflowing… And I could go 30 miles away from there and play in a theatre and there’d be a thousand people there. But at Janette Carter’s Family Fold it was: ‘oh, well that’s John from down the road. I see him at the grocery store every day. He’s good, but he’s a neighbor’. It’s the same thing everywhere. And in a way I think that’s really important though. It may be sad for the band because they can’t get big crowds in their hometown. That’s too bad, because that’s just the place where you’d like to get a big crowd. But at the same time a group like Jerrycan, or some of the other groups over here in Europe is going to make the music seem real to the average person who’s coming to a festival like this one. I think that a traditional country music artist can come from outside of the United States… But then again, I know Theo, he’s just… He’s my ‘neighbor’, so, if he can play that, maybe I can play that too. Or maybe I can play Dutch traditional music or maybe I can play French traditional music…

There’s one thing that I saw on your instrumental album, not the latest one, but the one before that, ‘Step by step’, that you have a song on it that is about Brabant. Is that right? How did you get that song? Is that in Holland?

Yes. Part of Brabant is in Holland and the other part is in Belgium. A friend of mine is very much into music from all over the world and has a little trio. Every Christmas they make a tape of their favorite tunes from that past year, and send it to their friends as a Christmas-card. And there were a bunch of Flemish tunes that were on this tape. I thought: ‘Oh, those are great’. At first when I saw the cassette I thought that the names of the tunes were great. I saw the name of this particular tune and decided that I had to learn that one. I thought: ‘I don’t care if it’s any good, but I love the title’. And I want to be able to get up on the stage and say: ‘here’s ‘The incredible giant steps from Brabant’… That’s where I got it from; a tape from some friends out in California.

It this your first trip to Europe? No, it isn’t the first time that I’m in Europe. It’s the first time that I play in Holland though…

You are married. How does your family cope with the fact that you travel as much as you do? It’s always been hard. Well, it’s a little easier sometimes. But as long as my wife has known me, or even before we were married this is what I did. So it wasn’t a surprise for her, she knew what she was getting into. And my kids of course… Well, daddy’s home, that’s the big surprise for them. But I try to when I go out… Well, I do 100 days of concerts a year and I don’t take extra days to travel. To me this is… I love it when I travel, and I like to see as much of a country as I can, or as much of an area. That’s my job, but my job is also being a father for our children and so I try to get home as quickly as possible to spend time with them. Because they’re little and they won’t be little for a long time. I grew up with a father who travelled, so I know how hard it is. I’m going to take six months off next year and I won’t travel and I won’t perform in that period at all. I just want to equalize things. But then… It takes a lot of understanding and a lot of talking, because kids change, and the funny thing is… I book about six months to a year in advance and so it’s better to be home for three weeks than to be on the road for six weeks. But by the time I booked all that time, six months later, when I’m actually doing all those bookings, my kids may say: ‘well, I wish that you were here during the week and just be gone on the weekends’. And then just make that change in your life, after a while it changes again. So it takes a lot of understanding on everybody’s part. I’m really lucky though…

That you make enough money to get the house paid for… My family is very understanding and they support all the things that I do which is very, very important because a lot of people that I know… Most of the musicians that I know, people who were married ten years ago, they aren’t married to the same people now…

How are your kids reacting to your playing? Are they… Do they show any signs that they will play music in their lives, or… Well, they’re both very good singers and they know all the words to all of my songs. It’s really funny sometimes, because just recently they’ve discovered that not everybody’s dad makes records and not everybody’s dad does this for a living. So they listen to my records now with a different set of ears. And I’m not foolish enough… By the time they’re teenagers they’ll think that I’m old-fashioned and weird and they’ll be embarrassed of their parents as I was when I was about fourteen. But I don’t want to push them. If they want to play, fine. There’s plenty of instruments around the house, if they have an interest in one…

Would you be disappointed if they didn’t pick up an instrument at all? No, not really. It certainly would be fun to be able to share a part of what I do with them, but… Well, both of them are real creative. I don’t know, it’s hard to make that kind of predictions. Because I can say: ‘no, I won’t be disappointed’, and then I’ll be…

You have your wishes of course… Well, I don’t depend on that to make myself feel like I’m a good teacher or something.

But the children can get a musical education of course. It’s important that kids grow up with lots of music, no matter what kind of music… Yes, we listen to a lot of different things. One day we’ll say: ‘let’s put on Bob Marley’. And the next day they’ll say: ‘put on ‘Sprout wings and fly’, which means they want to hear Tommy Jarrell. Or they want to hear some of my records or they’ll want to hear Bruce Springsteen or Prince or somebody… You know that music is a language and that there are lots of different dialects…

Are there some things that you can tell about your next children’s album? I believe it’s coming out very soon? Is it different from your first one? In some ways it is. One of the things about the first one is that there were lots of different kinds of music on it, and that will continue. I mean that there was some rock and roll, some zydeco…

The peanut butter songs was very popular with our kids…With this next one, I used the choir of the band that was used on ‘Gonna rise again’. This is a band that can both play electric stuff an acoustic stuff and we have some material that’s very Latin-sounding with muted hammered dulcimer, we have… My brother-in-law teaches retarded children in Los Angeles. He dis a songwriting class with his children, and they wrote some wonderful songs. One is called ‘I got a new car’, we did it with our rhythm and blues band with a horn section and everything. And the other one is a ballad called ‘Teddy bear’, and we do that in a reggae style… There’s some string band material that I’ve learned from Currence Hammonds and I do hambone on it and I do a lullaby. It’ll be a little more ‘produced’ than ‘Howjadoo’ was. But a lot of it is the same. We have the same person doing the cover…

Does it also have something special like the book in the last one? Yes, it also has a coloring-book inside and it has the chords to all of the songs on it and little stories and everything. And you know, there’s also songs in different languages and so on…

Did you practice a lot on the hammered dulcimer? You play a lot of different instruments, perhaps you had to work very hard on the hammered dulcimer… Well, I get a lot of practice by just being on stage. I don’t practice as much as I should though, I don’t think that anybody does that. A lot of the practicing that I do happens up here , in my head. Because the hammered dulcimer is the only instrument of which I feel that I have total control of it. A lot of time I’ll write tunes up in my head, or I’ll think of new techniques. And because I know the instrument so well, I can just go to the instrument and do whatever I wanted to do…

I read in a magazine once that there are some people that play in bluegrass bands, that study for hours on end… I never did that. I had ‘the bug’ so to speak, but I didn’t practice for hours and hours. I’d play for hours on end, but no scales or anything like that. I’d play tunes… You just have to have the instrument in your hands every day. Even if you play the same song every day… You mustn’t lose the feeling of the instrument…

Is it very difficult to play the hammered dulcimer? No it isn’t really. It’s a relatively easy instrument to learn how to play.

It sounds very difficult… Well, the things that I do are very difficult, but I’ve been playing the hammered dulcimer for fifteen years now. But I could take anyone of you here to the hammered dulcimer and teach you how to play a song in five minutes. Because it is very logical in its set-up, and your hands are doing the same thing. It’s the only instrument that I play where you don’t have to do one thing with this hand and the other thing with your other hand. Well, I should probably go and do this other interview.

Well, John, thanks very much for your time! Sure, sure…

Eem veur mien herinnern Harry. Het dit interview ook ooit in Strictly Country stoan? Bie mien waiten wel. Correct me when I’m wrong. Kin mie het concert in Diever nog goud veur de geest hollen. Zunsondergang: John op the hammered dulcimer mit een grandioze oetvoeren van ‘A satisfied mind’. Prachtig!!

Ik zat me hetzelfde af te vragen Bert. Heeft het indertijd in de Strictly Country gestaan? Ik vermoed van wel, maar ‘k weet het niet zeker (meer). Dat moment wat jij schetst van John McCutcheon bij zonsondergang aan het spelen op dat podium daar… Geweldig! Mooie tijden waren dat! Vond het ook leuk om terug te zien dat Theo Lissenberg ook meedeed met het stellen van de vragen. Af en toe denk ik te weten welke vragen van hem geweest zijn… Ben trouwens zo vrij geweest om McCutcheon’s uitvoering van ‘A satisfied mind’ bovenaan het interview te plakken.